Throughout history, tools of war have continually evolved. Some nations choose to innovate with technology while other, like Japan, innovated through technique. This focus on skills and mastering the use of weapons and human movement has given the world an art form that is as deadly as it is beautiful to watch – martial arts.

The rise of martial arts in Japan is linked to the role and importance of the Samurai, the military nobility and officer caste of medieval and early-modern Japan.

For most of the middle ages, Japan was ruled by Shoguns, military dictators that were appointed by the Emporer. Below Shoguns were Daimyo or High Lords. Below Daimyo were the Samurai, warriors who were regarded as far more important than the farmers, artisans and merchants that filled up the bottom three tiers.

Samurai were expected to be experts in a variety of battle techniques, both with weapons and hand-to-hand combat. Years were spent refining the smallest details. Kyudo or Japanese archery, for example, has an extensive list of guidelines to follow, from learning how to sit and hold yourself properly, how to dress in the traditional hakama or robe and how to tend for your bow.

For the Samurai, learning and understanding the craft was just as important as firing an accurate shot at your enemy.

It was this drive for perfection that inspired such terms as bujutsu, the science or craft behind the technique, and bugei or martial art. Both terms are widely used, along with the comparatively newer term Budo, which once meant a way of life that was both spiritually, physically and morally rewarding, but is now used almost exclusively to describe martial arts.

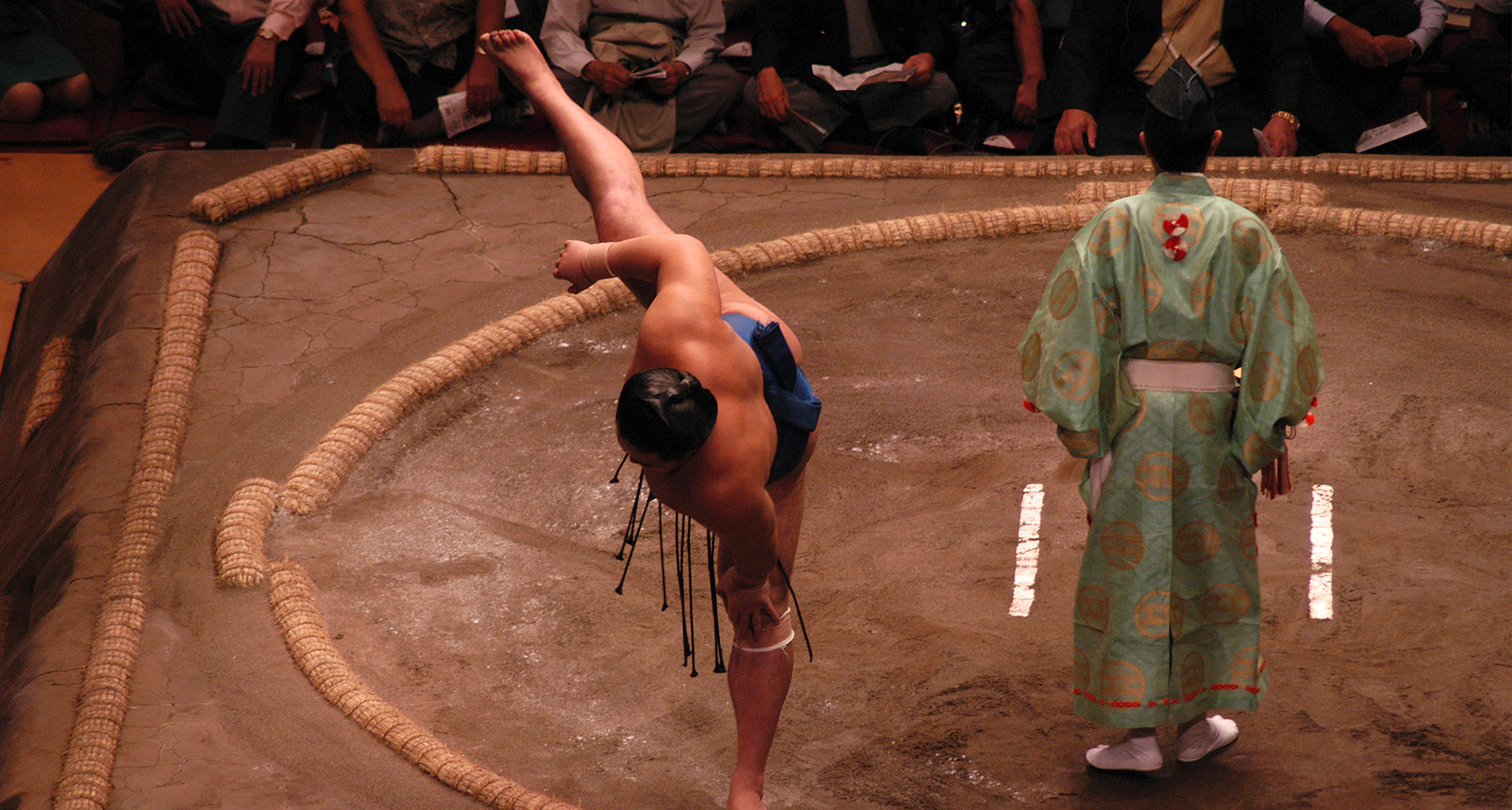

Religion has also played a key role in shaping martial arts, such as Sumo, which has strong ties to the Shinto religion. To this day, Sumo wrestlers still throw salt as they enter the ring to purify the area. Even the canopy draped over the ring, called a dohyo represents the roof of a Shinto shrine.

Before it became a competitive sport, Sumo was used to please the Gods or Kami and ensure a bountiful harvest. Although these original aims may now be buried under the competitive spirit of the sport, much of the tradition behind sumo remains intact. Sumo wrestlers still have to dress and wear their hair in a certain way, live in designated quarters and follow a strict code of conduct.

But martial arts did not only arise from warriors and religion, the Kanji for Karate can be translated to mean “empty hands” and refers to the farmers who had no formal weapons to use, but their methodical practise was no less intense than any other martial art.

A commonly employed distinction that can be made about Martial Arts is whether they fall into the koryu or gendai budo category, which means whether they came to prominence before or after the Meiji Restoration period.

This description of modern and traditional is not so easily defined, and there is some argument as to how you can date an art-form. One school of thought is that the “traditional” martial arts were for use in combat, while modern martial arts concentrate more on self-discovery and improvement.

Of course, many martial arts could encompass both of these, but some examples of Koryu Bujutsu would include sumo, jujutsu or any martial arts that employ katana or naginata (a long spear-like weapon).

Examples of Gendai Budo includes judo, kendo (a wooden sword is used) iaido, aikido or kyudo (as guns replaced bows, kyudo became less of a battle technique and more of an artform).

The ending kanji in all of the above Gendai Budo examples means “the way of…” so kyudo, for example, could be read as “the way of the bow.” Other Gendai Budo do not have this suffix, such as Karate, but if it ends in “do” it is more than likely a Gendai Budo.

There are far too many martial arts to list here, but almost all of them follow a common appreciation and dedication to both the hard method (goho) and soft method (juho). The hard method refers to direct attacks, or standing your ground whilst blocking attacks, whilst the soft method is far more subtle, avoiding attacks, or throwing your opponent off balance to use their own attack against them. Although every martial art approaches these methods in different ways, as the hard and soft methods mirror the Chinese idea of yin-yang, one is useless without the other, so both must be incorporated into teachings.